Building Social Apps with Mezzanine: Drum

标签:django, mezzanine, python, ormMezzanine has come a long way over the last few years, now powering hundreds of rich, content-driven sites. For the most part these sites follow a similar pattern, one which Mezzanine is heavily geared towards: B2C sites comprised of heterogeneous, hierarchical content. In this regard Mezzanine has been a huge success, however in its entirety it’s capable of quite a lot more. Out of the box it provides a range of useful utilities, that aren’t particularly geared towards a typical corporate site, but instead are aimed at a more social style of web application. These include things such as public user accounts with configurable profiles, threaded comment discussions, ratings, and much more - features that form the foundation of many of today’s most popular social web apps. This presents Mezzanine as a great foundation for building all types of social web applications, not just corporate, content-driven sites.

Interestingly, these extra utilities provided by Mezzanine form the core feature set of several very popular news aggregation sites, such as Hacker News and Reddit, and even their predecessors Slashdot and Digg. For those unfamiliar with these types of sites, they essentially provide crowd-sourced news, collectively controlled by contributing users of the site. Users create an account, submit links to interesting websites that they’ve discovered, and other registered users can then rate these links up or down - the end goal being that with enough positive votes, links are promoted to the front page of the site, gaining a ton of exposure. Users can then participate in threaded discussions which are provided for each website link, where comments themselves undergo the same crowd-sourced ranking, promoting the best comments to the top of the discussion.

To demonstrate these extra capabilities of Mezzanine, I set out to do something entirely lacking in innovation, by creating a direct Hacker News clone using Mezzanine. Creating a clone like this from scratch isn’t exactly a challenging task, and without doing anything remarkably different feature-wise, one that has little hope of gaining the type of traction that these sites enjoy. My intention here however, was to specifically explore how little work would actually be involved when leveraging Mezzanine as much as possible.

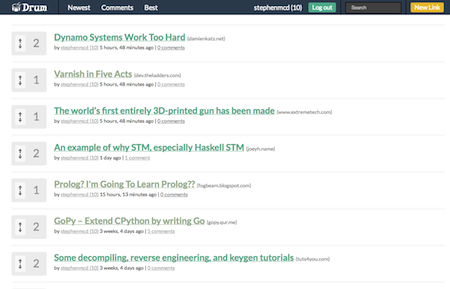

The end result is a project I’ve called Drum, and it turned out that by using Mezzanine as the foundation, each of the features required to implement a basic Hacker News clone required almost zero effort!

The remainder of this article assumes a basic understanding of Django, and will walk through what was involved in pulling each of these features together to create Drum.

Mezzanine is just Django: Links

The answer to many of the most frequently asked questions on the Mezzanine mailing list, often involves simply pointing people to the relevant section in Django’s documentation. This is one of the more commonly overlooked aspects of Mezzanine - it’s simply a standard Django project, and you’re free to implement your own models, views, templates, or any other component that Django provides.

With that in mind, we’ll get the boring stuff out of the way first, and put together some basic views and a model for the main content, namely the user contributed website links. Here’s our initial Link model:

from django.db import models

from mezzanine.core.models import Displayable, Ownable

class Link(Displayable, Ownable):

link = models.URLField()You’ll see we make good use of some Mezzanine building blocks here, even though we’re going it on our own. The abstract Displayable model is heavily used throughout Mezzanine. It provides all the common features needed for an actual web page, such as a title, a slug (the path portion of a URL), a published status and date, and meta data, which includes a description field we can expose to users when creating new links. The Ownable model provides the relationship between our links and the users who created them, so with all that in place, the only field we need to define initially is the actual link to the website itself.

Next up are our views for the Link model, again in plain old Django. We’ll use the generic views provided by Django, for listing, creating and viewing links:

from django.forms.models import modelform_factory

from django.views.generic import ListView, CreateView, DetailView

from .models import Link

class LinkList(ListView):

model = Link

class LinkDetail(DetailView):

model = Link

class LinkCreate(CreateView):

model = Link

form_class = modelform_factory(Link, fields=("title", "link", "description"))This is almost no effort thanks to Django’s generic views - the only deviation here is a custom form class in our create view, so that we can limit the fields that will be editable in the form used for submitting new links.

I can’t believe it’s Mezzanine: Threaded Comments and Ratings

Now we’ll start blazing through the Mezzanine features that require almost zero effort to apply to our project. Mezzanine provides the Django application mezzanine.generic, which houses several different utilities that can be generically applied to any Django model. Each of these use Django’s generic relations, and come in the form of a custom Django model field. Provided are things like keyword tagging, ratings, and threaded comments. We’ll start by adding threaded comments and ratings to our Link model:

from django.db import models

from mezzanine.core.models import Displayable, Ownable

from mezzanine.generic.fields import CommentsField, RatingField

class Link(Displayable, Ownable):

link = models.URLField()

comments = CommentsField()

rating = RatingField()All we’ve done here is added the CommentsField and RatingField fields to the Link model. Below is our link detail template, which will display the description given to the submitted link, and the threaded comment discussion following it. You’ll see it uses the comments_for and ratings_for template tags, to render the comments and rating widget:

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% load comment_tags %}

{% block title %}

<a href="{{ object.link }}">{{ object.title }}</a>

{% endblock %}

{% block main %}

<p>{{ object.description }}</p>

<p>{% rating_for object %} by {{ object.user.username }} {{ object.publish_date|timesince }} ago</p>

{% comments_for object %}

{% endblock %}These two template tags are Django inclusion tags, that use a corresponding template file to include in the page. This means we can override them in our project, in order to customise the way comments and ratings are rendered. For Drum, we’ll mostly leave the comment templates alone, but for ratings, we want to customise the template to display up and down arrows for voting, rather than the default form with numeric rating choices (1 to 5 by default in Mezzanine). But before we get to the template, we’ll first configure some Mezzanine settings in Drum’s settings.py module:

COMMENTS_USE_RATINGS = True

COMMENTS_ACCOUNT_REQUIRED = True

RATINGS_ACCOUNT_REQUIRED = True

RATINGS_RANGE = (-1, 1)The first setting COMMENTS_USE_RATINGS is just a basic flag that controls whether individual comments can be rated, which we want in Drum. The next two settings, COMMENTS_ACCOUNT_REQUIRED and RATINGS_ACCOUNT_REQUIRED are fairly obvious - we set these to True to ensure only registered users can add comments and ratings. The RATINGS_RANGE setting is the interesting one - it lets us define the range of valid rating values, which we specify -1 and 1 for, to represent a negative and positive rating. With that in place, we can now customise our rating include template:

<div class="rating">

<form method="post" action="{% url "rating" %}">

{{ rating_form }}

{% csrf_token %}

</form>

<span class="arrows">

<a href="#"><i class="icon icon-arrow-up"></i></a>

<a href="#"><i class="icon icon-arrow-down"></i></a>

</span>

<span class="score">

{{ rating_sum }}

</span>

</div>The template code here is almost identical to the default one used in Mezzanine. It displays the rating form (using the rating_form variable provided by the inclusion tag) and a value for the current rating (we use the rating_sum variable for this, but the inclusion tag also provides rating_count and rating_average, which is used in the default template). The real change we’ve made here though, is to add some links with up and down arrow icons, as well as some extra CSS classes which we can then use to hide the original rating form, and apply some JavaScript to the arrow links that submit the hidden rating form::

$(function() {

$('.arrows a').click(function() {

var arrow = $(this);

var index = arrow.find('i').hasClass('icon-arrow-up') ? 1 : 0;

var container = arrow.parent().parent();

var form = container.find('form');

form.find('input:radio')[index].checked = true;

$.post(form.attr('action'), form.serialize(), function(data) {

if (data.location) {

location = data.location;

} else {

container.find('.score').text(data.rating_sum);

}

}, 'json');

return false;

});

});As an added bonus, rather than simply submitting the hidden rating form, we post it via AJAX. Both the comment and rating views provided by the mezzanine.generic app know how to deal with AJAX requests, and will return an appropriate JSON response. In the case of ratings, the JSON response will include a location to redirect to, should the user needs to log in, otherwise it will contain the new rating sum, which we then use to update the visible rating sum directly in the web page, without ever leaving it.

Profiling Users

Now that we’ve got ratings and threaded comments hooked up, and restricted to registered users, let’s get users actually registering and logging in. Once again this is a breeze with Mezzanine, which provides the mezzanine.accounts app for implementing public user accounts. The accounts app provides all the features you’d expect, such as forms, views, and templates, for users to register an account, log in, update their account information, and more. Support for different sign-up flows such as requiring email verification, or manual approval by a staff member, are provided via the ACCOUNTS_VERIFICATION_REQUIRED and ACCOUNTS_VERIFICATION_REQUIRED boolean settings.

On top of that, Mezzanine’s accounts app is also fully integrated with Django’s Profile models. This means you can create a profile model associated with each user, and Mezzanine will pick up each of its fields and use them where applicable, such as the registration and account update forms. Mezzanine also defines the ACCOUNTS_PROFILE_VIEWS_ENABLED setting, which when enabled, will provide public profile pages for each user account.

With mezzanine.accounts added to the INSTALLED_APPS setting in Drum, next up we’ll define a simple profile model, that will allow users to provide a short bio and link to their own website:

from django.db import models

class Profile(models.Model):

user = models.OneToOneField("auth.User")

website = models.URLField(blank=True)

bio = models.TextField(blank=True)

karma = models.IntegerField(default=0, editable=False)You’ll notice we’ve also defined a karma field on the profile for each user, that can’t be edited via a form. Karma is an interesting feature of sites like Hacker News and Reddit, where the idea is to provide a score for each user that indicates their reputation on the site. Generally a user’s karma will increase as their links and comments are rated positively by other users, and decrease accordingly if the ratings given are negative.

With a karma field in place on our user profiles, all that’s left to do is update the user’s karma each time a rating gets saved or deleted, which we can do using Django’s model signals:

from django.db import models

from django.db.models.signals import post_save, post_delete

from django.dispatch import receiver

from mezzanine.generic.models import Rating

@receiver(post_save, sender=Rating)

@receiver(post_delete, sender=Rating)

def karma(sender, **kwargs):

rating = kwargs["instance"]

value = int(rating.value)

# Since ratings are either +1/-1, if a rating is being edited,

# we can assume that the existing rating is in the other direction,

# so we multiply the karma modifier by 2. Otherwise if the rating is

# being undone (deleted), then we just reverse the direction of the

# value to change karma by.

if "created" not in kwargs:

value *= -1 # Rating deleted.

elif not kwargs["created"]:

value *= 2 # Rating updated.

content_object = rating.content_object

if rating.user != content_object.user:

queryset = Profile.objects.filter(user=content_object.user)

queryset.update(karma=models.F("karma") + value)Time-scaled Ranking

All we’ve done so far is set up some basic crud features for our user-contributed links, and configure a handful of features provided by Mezzanine. We have one more requirement though, and I’ve saved the best for last.

One of the key ingredients of sites like Hacker News and Reddit, is the way ratings are used to rank link submissions and comments throughout the site. Links aren’t simply ranked by their overall rating, as this would lead to stale content on the site, where the most popular links of all time would remain at the top of the homepage. Instead, the ranking of links also takes their age into account. Ideally the most popular links should quickly rise toward the top of the homepage if they receive a high number of positive ratings, soon after being posted to the site. Links toward the top of the homepage would then gradually decline in their ranking, as their age increases, and as newer links are submitted that also receive a strong number of positive ratings.

A quick search online for how to implement this style of time-scaled ranking revealed a few different approaches, with varying complexity. I opted for one of the more simple algorithms I found, mostly because it actually works well, but also because it can be easily implemented in SQL, which means we can let the database take care of sorting results, and still make use of Django’s ORM and pagination.

from django.conf import settings

from django.utils.timezone import now

def order_by_score(queryset, date_field):

"""

Take some queryset (links or comments) and order them by score,

which is basically "rating_sum / age_in_seconds ^ scale", where

scale is a constant that can be used to control how quickly scores

reduce over time. To perform this in the database, it needs to

support a POW function, which Postgres and MySQL do. For databases

that don't such as SQLite, we perform the scoring/sorting in

memory, which will suffice for development. We also have a

date_field arg for controlling which field on the model represents

its creation date.

"""

scale = getattr(settings, "SCORE_SCALE_FACTOR", 2)

# Timestamp SQL function snippets mapped to DB back-ends.

# Defining these assumes the SQL functions POW() and NOW()

# are available for the DB back-end.

timestamp_sqls = {

"mysql": "UNIX_TIMESTAMP(%s)",

"postgresql_psycopg2": "EXTRACT(EPOCH FROM %s)" ,

}

db_engine = settings.DATABASES[queryset.db]["ENGINE"].rsplit(".", 1)[1]

timestamp_sql = timestamp_sqls.get(db_engine)

if timestamp_sql:

score_sql = "rating_sum / POW(%s - %s, %s)" % (

timestamp_sql % "NOW()",

timestamp_sql % date_field,

scale,

)

return queryset.extra(select={"score": score_sql}).order_by("-score")

else:

for obj in queryset:

age = (now() - getattr(obj, date_field)).total_seconds()

setattr(obj, "score", obj.rating_sum / pow(age, scale))

return sorted(queryset, key=lambda obj: obj.score, reverse=reverse)The above code first defines some different SQL snippets for converting date fields into timestamps, since this varies across different databases like PostgreSQL and MySQL. We also only define these for database back-ends that support a POW() function, as needed by our ranking algorithm. We then provide a fallback for any other database, where we don’t use SQL for ranking, and simply sort results in memory, which allows use to still use a database like SQLite during development, with a limited amount of data.

A feature like this might typically be implemented as a Django model manager, however since Drum doesn’t have control of the model for threaded comments, we implement this as a regular Python function, that we can wrap around calls to the model managers for links and comments. Here’s our previous LinkList view, with time-scaled ranking applied:

from django.views.generic import ListView

from .models import Link

from .utils import order_by_score

class LinkList(ListView):

def get_queryset(self, *args, **kwargs):

# Also call select_related on the user profiles, so we can

# display submitters' usernames and karma against each link.

qs = Link.objects.all().select_related("user", "user__profile")

return order_by_score(qs, "publish_date")Lastly, we want to apply our order_by_score function to the threaded comment discussion as well. At first glance this isn’t seemingly straight-forward, since these are entirely managed by template tags in Mezzanine, but with a little insight into how these work, we can achieve what we want quite easily.

The comments_for template tag we mentioned earlier is the one responsible for rendering a threaded comment discussion. It takes a parent argument, which to begin with is the object that has threaded comments attached to it - the Link model in Drum’s case. It then includes the comment template, which iterates through a single level of comments, displaying each one. For each comment, we then call the comments_for tag again, passing the comment in as the parent. This continues recursively, and is how the entire tree of comments gets rendered.

This might sound like a performance nightmare, if we assume each call to the comments_for tag performs a database query to retrieve a single branch of comments, however the tag is a bit smarter than this, and only queries the database when first called, building up the tree of comments and storing them in a template variable. Subsequent calls to comments_for then check for that variable, and reuse it if found.

Armed with this knowledge, we can easily create a template tag that mimics the initial call to comments_for, retrieving and building the comment tree, and storing it in the template context, prior to comments_for even being called. By using the correct variable name (all_comments), the first call to the comments_for tag will entirely bypass retrieving comments from the database, when it sees they’re already in the template context.

from collections import defaultdict

from django import template

from ..utils import order_by_score

register = template.Library()

@register.simple_tag(takes_context=True)

def order_comments_by_score_for(context, link):

comments = defaultdict(list)

qs = link.comments.visible().select_related("user", "user__profile")

for comment in order_by_score(qs, "submit_date"):

comments[comment.replied_to_id].append(comment)

context["all_comments"] = comments

return ""Here’s our link detail template again, with a call to the new order_comments_by_score_for tag, prior to comments_for being called.

{% extends "base.html" %}

{% load comment_tags %}

{% block title %}

<a href="{{ object.link }}">{{ object.title }}</a>

{% endblock %}

{% block main %}

<p>{{ object.description }}</p>

<p>{% rating_for object %} by {{ object.user.username }} {{ object.publish_date|timesince }} ago</p>

{% order_comments_by_score_for object %}

{% comments_for object %}

{% endblock %}Conclusion

That’s a wrap. Even for those unfamiliar with Django, it’s clear from the amount of code presented here how easy a task this was. Here are a few other features I implemented that aren’t covered here:

- Skinned with FlatUI and pjax

- Views for ordering all links by their age, all comments by age or score, and links and comments by individual user (from their profile page)

- Links also display the domain they’re hosted on (a method on the

Linkmodel) - To prevent duplicate links being posted, a duplicate will redirect to the original submission, until an expiry period has passed (a month for example)

- All usernames display their karma score, and link to their profile pages

- A Django management command for importing links from an RSS feed

What’s next for Drum? As I mentioned, the likelihood of the current demo gaining popularity is slim, however I think it’s an interesting step forward in the Mezzanine eco-system. Consider what would be required to turn Drum into a clone of other popular web applications:

- Reddit: Use Mezzanine’s keywords (already applied to our

Linkmodel via theDisplayablemodel) to break up the link listing view into individual views by keyword - Stack Overflow: Remove the link field from our

Linkmodel, and allow submitters to mark one of the related comments as correct - Every forum application under the sun: Remove the link field and ratings altogether, and apply some extra detail to our listing templates, like comment count and last commenter

The potential evolution of Drum becomes quite obvious: a general forum solution for Mezzanine, in the same way Cartridge provides ecommerce for Mezzanine. Are you interested in making this a reality? Check out the Drum source code and let’s make it happen!